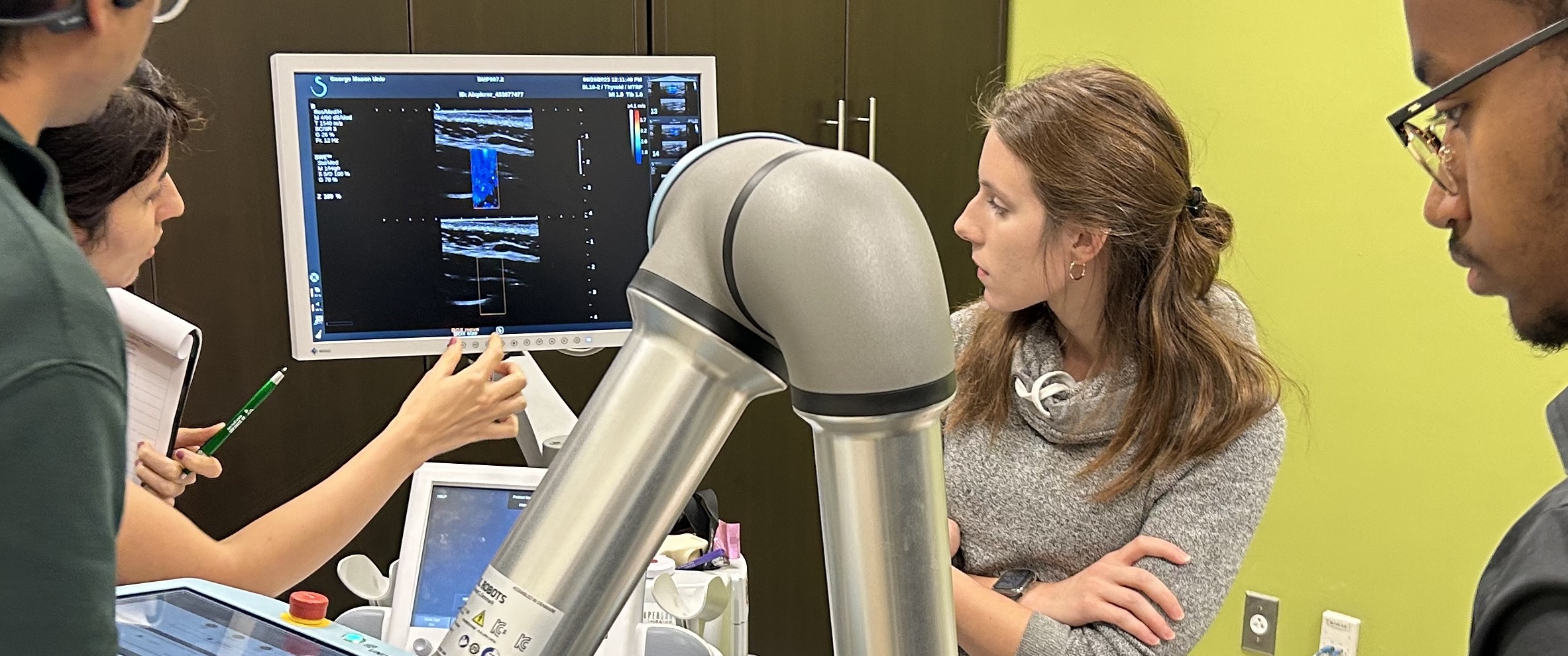

Welcome to the Neuromechanics Research Lab

We are an applied research lab at the intersection of neuroscience and biomechanics, uncovering how people move and engineering solutions for better health and function.

Recent Lab News & Blog Posts

- Morgan Lamarre proposed her MS thesis: Wearable technology for monitoring jump training intensity: a study of volleyball and dance movement profilesInjury prevention is of critical concern for collegiate athletes, as musculoskeletal injuries can significantly impact short-term performance and long-term career sustainability. Athletes will greatly benefit from knowing if they are at an increased risk of injury during their required high-impact… Read more: Morgan Lamarre proposed her MS thesis: Wearable technology for monitoring jump training intensity: a study of volleyball and dance movement profiles

- Brady Stinson-Smith proposed his MS thesis: Impact of assistive technologies on navigation for mobility-impaired studentsFor students with mobility impairments, navigating physical and social spaces on campus is often challenging, usually impacting not only accessibility but also inclusion within higher education. Although the ADA has guidelines in place, many of those who are mobility-impaired struggle… Read more: Brady Stinson-Smith proposed his MS thesis: Impact of assistive technologies on navigation for mobility-impaired students

- We presented 7 posters at the Biomedical Engineering Society annual conference (Baltimore, MD)We presented seven posters at the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) conference in Baltimore, MD this week!

- We presented 4 posters at the American Society of Biomechanics annual conference (Madison, WI)We presented four posters at the American Society of Biomechanics (ASB) conference in Madison, WI this week! Dr. Acuña also got to see old friends and colleagues from graduate school.

- Our senior design team won the People’s Choice Award at the GMU Undergraduate Research SymposiumEach year our lab mentors a senior design team, and this year they created a very impressive Virtual Reality Platform for Gait Rehabilitation. Congrats to Rasil Alamri, Lana Hashem, Rebecca Schuetz, Gavin Smiga, and Kirubel Tadesse for winning the People’s… Read more: Our senior design team won the People’s Choice Award at the GMU Undergraduate Research Symposium

- Our senior design team won the Outstanding Project Award at the GMU Undergraduate Research Symposium!Each year our lab mentors a senior design team, the project this year was to create a Myoelectric Prosthetic Arm Simulator as a Research Platform and Outreach Tool. We presented this project at the College of Engineering & Computing Undergraduate… Read more: Our senior design team won the Outstanding Project Award at the GMU Undergraduate Research Symposium!